- About

- Staff

- Issue 1 (Deaths)

- Issue 2 (Bodies)

- Issue 3 (Quests)

- Issue 4 (Institutions)

- Issue 5 (Beldams)

- Issue 6 (Seas)

- Issue 7 (Skins)

- Issue 8 (Dreamings)

- Issue 9 (Architectures)

- Issue 10 (Governments)

- Issue 11 (Possessions)

- Issue 12 (Animals)

- Issue 13 (Births)

- Issue 14 (Musics)

- Issue 15 (Diseases)

- Issue 16 (Trades)

- Issue 17 (Gothics)

- Issue 18 (Magics)

- Issue 19 (Voyages)

- Issue 20 (Birds)

- Issue 21 (Cocktails)

- Issue 22 (Archives)

- Issue 23 (Battles)

- Issue 24 (Botanicals)

- Issue 25 (Prehistories)

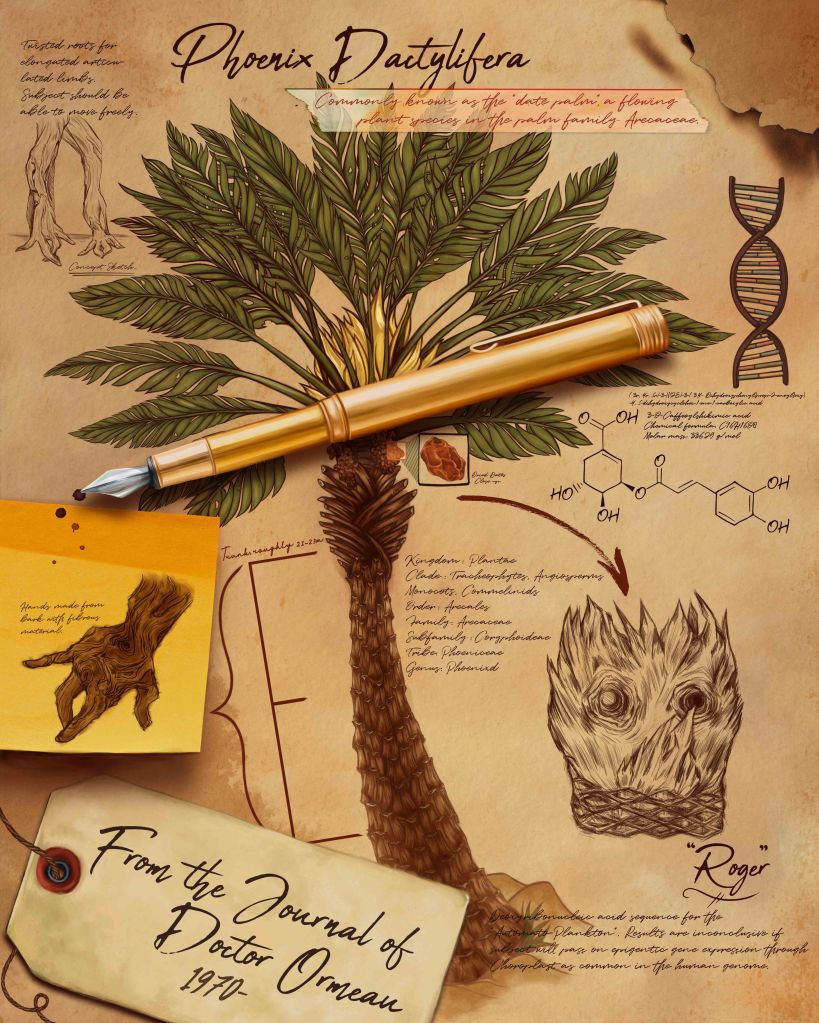

Dr. Ormeau’s Botanical Menagerie, by Morgan L. Ventura

The following is an assemblage of newspaper clippings, letters, court transcripts, and ethnographic logs from both Dr Sidney Ormeau, a botanist, and Dr Agnes Fortune, an anthropologist dispatched by the United Nations to investigate the situation. Everything pertains to the case of Dr Ormeau’s Botanical Menagerie v. the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

*

Clipping from The London Times:

ANARCHIST AND BOTANICAL ENGINEER, SIDNEY ORMEAU, CREATES RACE OF ‘AUTOMATO-PLANKTON’ IN THE AEOLIAN ISLANDS

BELFAST, February 21, 1973—

According to Mrs Elizabeth Ormeau, the mother of Dr Sidney Ormeau, her son fled Belfast amidst the start of the Troubles for Sicily, settling on one of its famously striking Aeolian islands. Educated at Trinity College Dublin where he read chemistry, philosophy, and botany, Ormeau received his doctorate in botany at Oxford University. Mrs Ormeau reports that she has received phone calls from Aeolian residents stating that Ormeau purchased land on Stromboli and is practising an illicit, dark activity.

Residents claim that Ormeau has discovered a way to animate plants, bringing them to life to live as humans. He purportedly engineered a cluster of neon sea plankton so it would grow to be five feet tall, serve as a portable lamp, and make him tea. Not without a sense of humour, he has taken to calling this abomination his ‘automato-plankton’.

Aside from this automato-plankton, there have been recent reports of a palm tree travelling between his compound and Stromboli’s centre to purchase sundries for Dr Ormeau. This sentient palm tree goes by the name of Roger.

*

From the Ormeau family archive, donated to the University College Dublin:

Log #12

STROMBOLI, SICILY, 30 March 1973

Clearly, I cannot speak to my own mother without her airing everything to news outlets. What the media does not understand is that my work is not a mad experiment or evil conspiratorial enterprise. Far from it, my work is about class and ecology. We’ve seen the rise of robotic engineering and how this has been harnessed to replace the need for humans to work in dangerous factory conditions. The problem with robots, however, is that their creation demands continuous extraction of finite resources, polluting and destroying the planet, whereas my approach mobilises what we already have here, living amongst us—our friends and relatives, the botanical kingdom! I’ve found a way to alter the plants around me, ever so slightly. With only the smallest changes to their deoxyribonucleic acid nucleotides, I’ve given them speech, made them robust, and gifted them human mobility. They can be the new automatons! These plants are capable of everything a robot can do—and more! I never feel alone when I’m with them, but more than anything, they’re incredibly intelligent. Roger, previously a palm tree I found near the shore when I first arrived, has grown into a fine specimen, with a passion for the poetry of Pablo Neruda and fiction of Virginia Woolf. Roger prefers to remain without a gender. They travel into town for me to pick up whatever I need. The media questions the ethics of my work, but the local residents seem quite complacent with it.

*

April 17, 1973. Hi, this is Roger. I’m a date palm, originally named Phoenix dactylifera, from a beach on Stromboli, Sicily. Today is very rainy, so Dr Ormeau kindly taught me how to use this type-writer. I love words, I love poetry. I cannot thank Dr Ormeau enough for giving me speech, for giving me these hands, although they are nothing like his. Far from delicate, my hands are rough, covered in small, brown roots and hair. I wish I had Dr Ormeau’s hands. I wish I had his mouth, with its pink lips and shiny teeth. Mine is too large, protruding like a prosthetic limb from the middle of my trunk. Us plants look very different from Dr Ormeau. Vespa, whom he made from neon plankton, is beautiful. They glow in the dark like the moon, a vibrant tangerine-pink, and they are always blooming as they speak to me. I can hear everyone’s thoughts, even Dr Ormeau’s. His are very hurried, very worried. What is labour? What is love? Love, ROGER.

*

From the files of Dr. Agnes Fortune:

22 May 1973

Dear Antonio,

I reckon that you read Dr. Sidney Ormeau’s recent article, “Botanicals against materials: A prolegomenon to human and plant relations in the 20th century,” in the Journal of Ethnobotany, which is astoundingly misplaced and misinformed. It’s mostly a love letter to plants, which is fine, but that should never be the crux of an academic article. It should’ve been called, “Plants Are My Friends,” and run as a memoir in the Paris Review. Yet are plants really Dr. Ormeau’s friends? I don’t believe so. Ormeau alters their genes in order to “amplify their sentience,” harness their intelligence and compassion, and seduce them into subjugated positions. He’s very much using his plant friends. He’s pioneering what he’s dubbed “Botanical Engineering” to fulfill his own desires and pander to his innate indolence.

I agree with the principles of Marxism. I understand that part of Ormeau’s perverted research is framed as a socioeconomic intervention where the plants will take on the labor—the burden of the working class. But if we really sit down and think about it all: if plants are, indeed, already vital, sentient, and intelligent creatures, isn’t Ormeau’s endeavor a major ethical violation? Isn’t he actually engaged in the business of oppressing a whole new class, creating an even weirder set of relations? Just look at the “automato-plankton” he’s made.

I’m obviously concerned about Ormeau and his “practice.” Though, from what I’ve heard down the pipeline, UNESCO has eyes on Sicily’s Aeolian Islands through their new World Heritage program. If the Aeolian Islands should become a World Heritage Site, well… I imagine Ormeau may be forced to move.

Sincerely yours,

Agnes

*

June 5, 1973. Hi, Roger again. It’s nice of Dr Ormeau to let me rest on these rainy days. I don’t have to run to town today, but the others must still work. Vespa always works. They provide Dr Ormeau with light. “A green lamp,” he calls Vespa, and he enjoys working late into the evening. Vespa talks to me as they work, and I hear them through these thin, chalky walls. Dr Ormeau doesn’t seem to always hear us when we talk, like right now, when Vespa is singing to me from Dr Ormeau’s bedroom. At first, we thought he might be partially deaf, but we realised that, although we now have these new mouth-parts that give us human speech, we’ve maintained our former language of telepathy. We have two languages then.

Why do we work so much? I love Dr Ormeau, he has opened up the human world to us, and he teaches me about history, philosophy, poetry, and the concept of ‘class’. He wants the working class to be liberated, and talks of humans reaching a point where they won’t have to labour and can pursue purely creative acts. He’s created us—there are 11 of us now doing all sorts of ‘jobs’, but I was the first. I want to create. We all want to create. Vespa wants to compose music, I want to write poetry; why doesn’t Dr Ormeau see how these passions transcend species? Dr Ormeau says he left a warzone and wants to see a future where humans stop hating each other and love one another. His mind says this, too, so we believe him. I see how this connects, but I also feel deep in my roots that there’s something else. Love, ROGER.

*

From the files of Dr. Agnes Fortune:

Field Note #1

22 July 1973

Today I left UNESCO’s headquarters in Paris for Sicily, stopping over briefly in Palermo before taking a rusted water-plane to Stromboli. I’ve never been to the Aeolian Islands nor mainland Sicily, but I’m already bewitched by their jewel-like beauty. On the journey to Stromboli, it was difficult to not marvel at the pristine quality of these islands, their rustic, volcanic landscape jutting towards a crystal-blue sky, blanketed in lush vegetation.

I’m anxious about being in Stromboli and staying with Sidney Ormeau, but UNESCO will not budge: according to the Director-General, Stromboli must, at all costs, be inscribed as a World Heritage Site. He insists that the Aeolian Islands are exemplary natural landscapes—they’re untarnished by industrialization and carry a cultural significance. The Aeolian Islands are fixtures in Sicilian mythology. This isn’t my area of expertise, but UNESCO aims to nominate and preserve any site “of outstanding universal value” that’s important to human memory and meets certain criteria. Some of these criteria are ambiguous, like this notion of “integrity” that was proposed by several countries, while others are more self-explanatory. It’s easy for anyone to discern why a site might have significance with a bit of research—so much of our world is imbued with multiple meanings; nearly every monumental heritage site has a sacred or religious dimension, or was once a site of power.

I’m supposed to ask Ormeau to leave Stromboli. His presence, alongside his illicit activities “engineering” new botanicals, disrupts Stromboli’s landscape and negates its value. Ormeau literally pollutes this future heritage site. I don’t think it’ll be easy. We already sent Ormeau two letters asking him to leave and take his activities elsewhere. No response. I did receive a type-written letter from someone named Roger, who I’ve now discovered, as of today, is a sentient date palm. The letter didn’t make much sense; instead, it asked UNESCO for clarification on its acronym. The Director-General said to not write back.

Ormeau’s estate is 50 hectares. Its architecture blends Spanish styles with a bleak, almost Brutalist aesthetic. The smaller edifices spiral outward from his own dwelling. These smaller buildings resemble make-shift casitas with corrugated iron roofs, designed for his “botanical menagerie.” I think that’s what it should be called. Ormeau’s plant-friends are a strange bunch, a collection of botanical specimens that he’s now keeping indoors, basically imprisoned.

Ormeau gave me a warm welcome—and looks nothing like I imagined. Tall with a slight build, dark hair, and weathered skin, he looks older than what I’d have thought. His eyes are small, and they glimmer with either suspicion or mischief. Upon my arrival, he embraced me and had Ingrid take my luggage, offering me a room in his own house. “None of the casitas are fit for humans,” he told me, gesturing to a dozen structures looming beyond us (at sunset, their shadows bleed into the crimson and violet sunset). An impressive dinner was spread before me featuring Sicilian pastas and fresh vegetables. Some of the plants ate with us, their new mouths quivering as they navigated chewing and swallowing like Ormeau and I (the acoustics of these plants eating sounded like sheep masticating on an unsettling combination of mushy tomatoes and bones), while several hung overhead to provide light. These were examples of the “automato-plankton” I’d read about. One of the automato-planktons, who’s named Lu, is bright yellow with turquoise splashes; their tentacles emanate with a golden light. The other automato-plankton that was present is called Vespa, who arranges themself in the shape of a lamp, an incredible example of botanical mimesis.

There’s always more to write, but I need to rest. Tomorrow Ormeau gives me a tour of his lab.

*

July 22, 1973. Hi, it’s Roger. Today another human arrived who’s called Doctor Agnes Fortune. She is a doctor of anthropology. She claims to be interested in human-plant relationships; this is what she tells us and it’s also what Dr Ormeau believes. I know she works at UNESCO. I wrote to UNESCO after receiving two letters from them asking all of us to remove ourselves from Stromboli because they wish to make most of this island a World Heritage Site. Dr Ormeau doesn’t know this, it would upset him very much if he knew, as he thinks of Stromboli as a home. I feel terrible that I never gave him the letters, and now Agnes is here and Dr Ormeau thinks this is because she’s interested in his work. UNESCO never answered my letter, but with Agnes here I can find out more. Agnes brought 10 books with her, including a large red one called ‘Capital’ by Karl Marx. She let me borrow it. I’ll begin reading tonight. Love, ROGER.

*

From the Ormeau family archive, donated to the University College Dublin:

Log #37

STROMBOLI, SICILY, 23 July 1973

Dr Agnes Fortune arrived last night from Paris. She’s an American through and through: abrasive, charming, intelligent, and beautiful in the ways she comports herself as if she owns the world. At the same time, we all know that’s also unattractive, exemplary of that snotty American exceptionalism, but Agnes makes up for it in her curiosity and the shroud of insecurity that she lugs around.

This afternoon, I gave Agnes a tour of my laboratory. She referred to my estate as a ‘botanical menagerie’, which I must admit, has a certain ring to it, though it also implies imprisonment. I don’t think the plants feel that way at all. They are all extremely happy. Well, except for Roger, who grows more anxious every hour. They spent the entire day following me around, wringing their hands while their tiny teeth chattered and their palm fronds shivered in 37 degree heat. Absolutely mind-numbing.

Agnes asked me to show her how to engineer the plants so I demonstrated with a prickly-pear cactus. She also asked me if I had permission to do this, if these plants had asked for human-like sentience, which is, frankly, a hilarious question. Of course they’d want this. Roger and Vespa have never indicated otherwise. I explained the engineering, but in such a way as to not overburden Agnes. It’s an invasive, gruesome process. Yet the reward is beautiful, with the plant fully blooming, entering into a new state-of-being soon after due to its altered physiognomy (its limbs and mouths for mobility and language, respectively). It’s a complete ‘re-orientation’, if you will.

Anyway, the cactus will be ready in a few days and I’ll assign it a job. Meanwhile, Vespa has been unusually unruly. Instead of providing reliable light, they keep flickering. Vespa claims they’re exhausted, but I engineered all these plants to be hearty and without any need for rest. Vespa also claims that they and the other plants want to pursue ‘a vocation’ rather than a job that is ‘pure, onerous labour’. You’d think they were reading social theory!

*

From the files of Dr. Agnes Fortune:

Field Note #3

24 July 1973

I haven’t asked Sidney to leave yet. It’s hard to find a moment to speak with him privately—he’s always being shadowed by Roger and Vespa. I gave Roger Marx’s Capital and some books by Max Weber because I think this botanical menagerie should know how capitalism works. Despite Sidney’s purported “good intentions,” he’s honestly swapping one system of oppression for another. Yes, plants are already vital and sentient in their own way, but assuming they wish to exist under a paler shade of capitalism is presumptuous and rude.

Sidney continues to think that I’m here to scope out a new ethnographic field-site. I’ve tried to explain to him that I don’t speak Italian, and that my previous research examined the politics of tourism at a Peruvian archaeological site. I guess there are some similarities? Both of these contexts are concerned with heritage and labor.

Over dinner tonight—which was phenomenal as usual with squid ink pasta, elaborate platters of eggplant, golden garlic, greens, and wine—Roger asked what “to unionize” means.

“I cannot find a definition of it in the dictionary you have here, Dr. Ormeau,” they said to Sidney.

Silverware dropped from Sidney’s hands, emitting an irritating, metallic clang against the table. Vespa’s glow dimmed as Sidney looked first at Roger and then out the window into the distance. I could tell he was thinking, grasping for words, but the room felt impossibly heavy—and not from Stromboli’s high humidity.

“Dr. Ormeau, why would that be?” Roger pressed.

“Roger, I don’t know,” he said, avoiding Roger’s gaze.

Roger’s palm fronds started shivering again, detaching a few fresh dates in the process. They got up from the table and left the room only to return a moment later with a thick copy of a dictionary from the 1930s.

“Look,” Roger said, showing Sidney the page—well, the page where it should’ve been.

“Ummm…”

“Yes, it’s missing,” Roger snapped at Sidney. “Why would it be missing?”

“Roger, my dear,” laughed Sidney anxiously, “this dictionary was passed down to me from my mother when she was in college… If the page is missing, then—”

Roger let out an exasperated sigh. “I want to know, Dr. Ormeau. We want to know. You must tell us!”

As Roger spoke, Vespa’s many parts brightened, illuminating the room with a stark white light that made everything appear over-exposed, before dimming once again. I felt extremely uncomfortable.

“Sidney,” I said. “Why don’t you tell them?”

Sidney couldn’t look at me either, averting his gaze to stare pointedly at his dinner plate.

“Also, please tell us about the Teamsters,” Vespa rasped.

I froze as Vespa said this. Sidney began to shake. We finally exchanged a look.

He leaned over and whispered, “Agnes, what are you actually doing here? What have you told these plants?”

I couldn’t find an answer. Because, yes, I had given them reading materials, but neither Marx nor Weber talk about unionization or Teamsters. Unless…

“We can read your thoughts,” Roger said, breaking the silence. “In case you are wondering. I think you humans call it ‘telepathy.’ It’s our original language. Botanical language. A beautiful way to communicate. We always know how one’s heart truly feels about any matter.”

“Damn it, Agnes, why would you even be thinking about unionization and the Teamsters?”

I shrank into my seat before straightening back up again. I would not let this man tear me down. “Because, Sidney Ormeau, I believe in workers’ rights and fair wages. And when I see any sentient being working, I can’t help but want the very best for them.”

“So, you have been thinking about these things?” Sidney confirmed.

“Who are the Teamsters? What is unionization?” Dr. Ormeau’s entire botanical menagerie sang in unison, a creepy chorus, as they crowded both exits of the dining room and Vespa dimmed their light further so they were barely emitting a pallid glow.

“Answer them, you fabulous scientist, you giver of life, Dr. Ormeau!” I shouted at Sidney.

Sidney gritted his teeth, but then finally, amid the last glimmer of light from Vespa, answered his children, offering a simplistic definition of both. He’s furious with me but didn’t ask me to leave. Perhaps he’ll ask me tomorrow.

“Agnes,” Sidney said as I squeezed past several plants to retire for the night, “meet me tomorrow at 11am for tea. Watch your thoughts, please.”

*

July 25, 1973. Hi, Roger again. I can’t decide if I like Agnes or not. It seems she’s stirring up trouble, but doing so from the bottom of a good heart. Dr Ormeau finally told all of us what to unionise means and about ‘the Teamsters’. We’ve formed a botanical union now. Vespa chose the name ‘the Plantsters’. Tomorrow we will ‘bargain’ with Dr Ormeau for better control over the hours in our workday. Love, ROGER.

*

From the Ormeau family archive, donated to the University College Dublin:

Log #40

STROMBOLI, SICILY, 26 July 1973

If you’d ever told me that I would one day be bargaining with a coterie of plants for ‘workers’ rights, I’d have told you to catch yourself on. Yet, alas, here we are. Today Roger, Vespa, and their friends, collectively referring to themselves as ‘Plantsters’, asked for 8-hour caps on shifts. ‘Outrageous’ is what I told them, which did not go over well. Vespa’s light turned a nuclear orange and then shut off. The entire compound is now without light as they have gone on permanent strike.

Clearly, Agnes must’ve planted the seed in their botanical brains that labour can be negotiated and that capitalism is a system that can be manipulated, even dismantled. I see my work in botanical engineering as improving the human condition, altering capitalism so it harms us less, but Agnes obviously believes it’s another form of systemic oppression. I just don’t agree. While plants are, indeed, sentient beings, and I’ve harnessed their intelligence and compassion, I don’t see why they’d need to be treated as beings with human needs.

I asked Agnes to leave Stromboli today over tea. She then asked me to leave—can you believe it? My guest, whom I allowed to stay here free of charge and entertained these last several days, has the nerve to ask me to leave Stromboli, abandoning what is my life’s greatest work? She also said these were orders from UNESCO, a branch of the United Nations. I know nothing about the UN save for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which is a charter humans flagrantly ignore in practice—though in theory it’s grand, so?

I refuse to leave. Who would care for the plants? Agnes claims that my presence is a ‘violation’ and that my plant creations and I ‘endanger’ the status of this soon-to-be-inscribed World Heritage Site because we ‘tarnish the purity of the environment’. You might as well tell us we are a pestilence on this Earth!

After our altercation in the parlour, Roger entered to say, ‘I tried to tell you’, and oh, I will tell you. I will tell you how you should’ve told me. Why didn’t that stupid plant tell me Agnes’s intention, rather than concerning themself with unionisation, philosophy, and poetry? Instead, they went about reading Marx— surely a book Agnes gave them!

How can I get rid of Agnes? I will not let UNESCO displace us.

*

July 26, 1973. Roger here. Vespa, myself, and everyone are on ‘strike’. We refuse to work for Dr Ormeau, whom we think is very selfish, until he finds more compassion in his withered soul. He talks of his needs, but doesn’t acknowledge our needs, the needs of his kin! ‘You think plants are people, too!’ he said, roaring with laughter. I’m deeply wounded by how he found comedy in this statement. We aren’t people but we deserve to be treated well. I know there’s love inside Dr Ormeau, but like any deprived flower, it’s wilting. He had an altercation with Agnes because he wants her to leave but she finally told him the truth on how she works for UNESCO and needs him to leave instead. We don’t want either of them here if they cannot be kind, but it’s true that Dr Ormeau made us and we are indebted to him. Agnes is not bad, though—she is at the mercy of this UNESCO. She taught us about capitalism and human rights. Tonight I heard Dr Ormeau mention a Universal Declaration of Human Rights. What about plants? I think there’s a solution, but it’ll never feel right. Love, ROGER.

*

From the files of Dr. Agnes Fortune:

Field Note #6

26 July 1973

I asked Sidney to leave today after he invited me to tea in the most hilarious attempt to “code” him asking me to also leave. He was incensed by my presence as a UNESCO delegate and accused me of espionage and betrayal. Neither really holds up, honestly. I’m an anthropologist, I was dispatched to Stromboli to understand Sidney’s illicit “scientific” practice so we could find a way to ask him to leave. You can’t just waltz into a place and demand someone leave without comprehending their personality and agenda. Sidney’s a narcissistic, self-aggrandizing, hypocritical “anarchist,” yet the only anarchy I’d attribute to Sidney is the perverted manipulation of sentient beings in every way imaginable. He’s twisted reality in order to deify himself. To think that replacing all labor with a sub-class of indentured sentient plants is the panacea to society’s ills is the biggest lie ever, and at least now, Roger, Vespa, and the rest of Sidney’s botanical menagerie are cognizant of this.

Since he asked me to leave, I’ve planned to take the water-plane back to Palermo tomorrow afternoon. Coupled with the unsigned letter I found on my bed asking me about the UN Declaration of Human Rights, it’s wise to flee. Maybe Stromboli should be left alone. This place is absolutely bonkers.

*

Clipping from The New York Times:

UNESCO ANTHROPOLOGIST, AGNES FORTUNE, AND ROGUE SCIENTIST, SIDNEY ORMEAU, FOUND POISONED ON DINGHY IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

PALERMO, July 29, 1973—

Twenty miles off Sicily’s east coast, a fishing crew found a small wooden dinghy, The Vain Lad II, carrying two unconscious individuals, who were later identified as Dr. Agnes Fortune, an anthropologist from UNESCO, and Dr. Sidney Ormeau, an anarchical scientist, notorious for his botanical engineering of sentient plants. Both Fortune and Ormeau were found with unusually high levels of a marine toxin from plankton in their blood. Fortune regained consciousness in Rome and traveled back to Paris where she has checked herself into a mental asylum. Dr. Ormeau also survived, but received a court summons from UNESCO for a set of violations related to his botanical beings and fled. His whereabouts remain unknown.

*

Dr Ormeau’s Botanical Menagerie v. the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (ICJ-126 B.R. 398)

18 September 1974

International Court of Justice

Trial Chamber V(b) – Courtroom 1

Situation: Italy

Judge Junko Murasaki

COURT USHER: All rise. The International Court of Justice is now in session. Please be seated.

JUDGE MURASAKI: Good morning. Could the court officer please call the case?

COURT OFFICER: Thank you, Madam President. The situation is in the Republic of Italy, and the case is Dr Ormeau’s Botanical Menagerie against the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, ICJ-126 B.R. 398. We are in open session.

JUDGE MURASAKI: Thank you. Yes, counsel, please introduce yourselves, starting with the plaintiff.

ROGER THE PALM: Your Honour, my name is Roger the Palm. With me today in court are Vespa and the other members of Dr Sidney Ormeau’s Botanical Menagerie. Thank you.

JUDGE MURASAKI: Thank you. Defence team, please?

MS. HIGGINS: Thank you, Madam President. I’m Veronica Higgins of UNESCO. I’m representing the entirety of UNESCO and its interests.

JUDGE MURASAKI: Thank you, and welcome. Plaintiff, please.

ROGER THE PALM: Thank you, your Honour. We stand here before you because UNESCO wishes to forcibly remove us from our home, at once both displacing us and dispossessing us of our land, resources, and livelihoods. UNESCO seeks to inscribe Stromboli as a World Heritage Site yet claims it cannot do so unless we leave because we are not “pristine representatives” of the plant life in Stromboli’s natural landscape. We cannot help that we are like this. Dr Ormeau made us this way. We also believe that we are entitled to a set of rights, as workers, as sentient beings. Stromboli is not terra nullius or empty land to be declared collective heritage; it is our home. We ask that UNESCO and the UN recognise two things: one, that we, as plants, deserve a UN Declaration of Plant Rights, and two, that as sentient, living beings, we should be allowed to remain in our home and not treated as some kind of abomination.

JUDGE MURASAKI. Thank you, Roger. Defence, what say you?

MS. HIGGINS: UNESCO does not recognise the request, counsel, or existence of Dr Ormeau’s Botanical Menagerie. To us, this is a trial against an absence, a ghost, an inanimate entity. In other words, this is a moot point, or rather, these are two moot points that are non-negotiable. Plants are not people, and even though I might acknowledge that we are sitting in a court with a date palm that’s been given human speech, UNESCO rejects this as it does not fall within our purview.

JUDGE MURASAKI: Thank you, Ms. Higgins. It seems you are saying you do not acknowledge the validity of this case.

MS. HIGGINS: We do not. And we will proceed with removing Dr Ormeau’s Botanical Menagerie.

ROGER THE PALM: If I may, it seems that UNESCO—and now this court—is attempting to regulate the distinction between life and non-life, as if you are some kind of god, when in fact humans are far from it, and are rather hopeless beings who go around dictating what is fact or what is fiction when these boundaries are only governed by your own limited capacity for imagining. To relegate us to the margins when you clearly acknowledge our existence enough to displace, dispossess, and destroy us is not an act of God, but an act of ignorance and cruelty. May I not be the judge.

[REDACTED]

*

November 11, 1974. Hi, it’s Roger. It’s been a while. I’ve moved with Vespa and the others to Berkeley, California, because we heard it has a nice climate and liberal politics. We’re all disappointed in UNESCO and the International Court of Justice. I think there’ll never be justice for us plants. But maybe that’s because justice doesn’t exist for humans either. Do they even know what it is, or how it should work, or what it means? Do they ever give each other justice? It would seem no. I look around me and all I see are pain and suffering, humans wounding one another in the name of this or that. Yet there’s love, too, and it’s in their poetry, their art, their cinema, and between themselves when no one’s quite looking. We haven’t found Dr Ormeau; I suspect he’s returned to Ireland, but I now see why he made us and tried to have us labour in humanity’s place. What if a society revolving around art was the only way to find love, to enact justice? How can we ever achieve this under these conditions? I remain uncertain. Someone please show me. Love, ROGER.

*

Story copyright © 2021 by Morgan L. Ventura

Artwork copyright © 2021 by Marlo Musa

Morgan L. Ventura is a Rhysling-nominated and award-winning poet, writer, and anthropologist based in Northern Ireland. Ventura’s poetry and fiction have appeared in Strange Horizons, Augur, and Bending Genres, among others, while their nonfiction can be found in Best Canadian Essays 2021, Geist, and Folklore Thursday.

Marlo Musa is an illustrator currently living in the Pacific Northwest, but their heart will always be in their childhood city of San Francisco. Marlo creates their art using very fine line work with a focus on detail, symbolism, and a painterly touch. They strive to make art that explores the ability to transform the intangible into a visual form. They have previously had their work shown in several indie zines, including but not limited to The Penumbra, Old Fashioned Lover Boys, and Carpe Noctem.